Create and present an impactful user research case study

How to stay sane while navigating the case study journey

👋 Hey, Nikki here! Welcome to this month’s ✨ free article ✨ of User Research Academy. Three times a month, I share an article with super concrete tips and examples on user research methods, approaches, careers, or situations.

If you want to see everything I post, subscribe below!

The first time I created a user research case study was back in 2014. I had no user research experience and, quite frankly, had no idea what I was doing. The only thing I did know was that I wanted to be a user researcher (thank goodness I got that right).

Before that moment, I had a few jobs as a tennis instructor, a bartender, a retail sales worker, an academic research assistant, and a personal assistant to a successful businesswoman.

Never in my life had I ever needed a case study. I didn’t even know what a case study was until I started applying to user research jobs. Back in that day, you didn’t always need to send in a case study or portfolio when you applied, but I quickly found that you needed to present a case study.

In fact, I learned I needed to present a case study about two days before my interview. Yipee. That was a fun-filled frenzy of caffeine, pizza, and, I’m not going to lie, some wine. What I created is something that now makes me cringe:

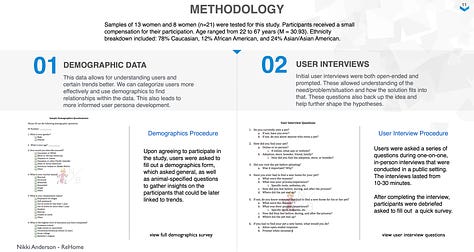

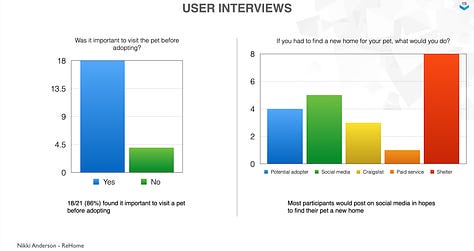

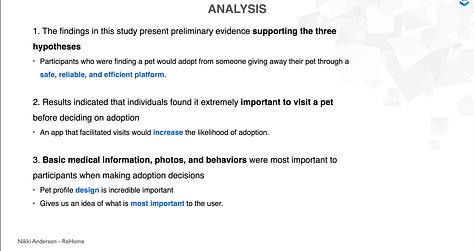

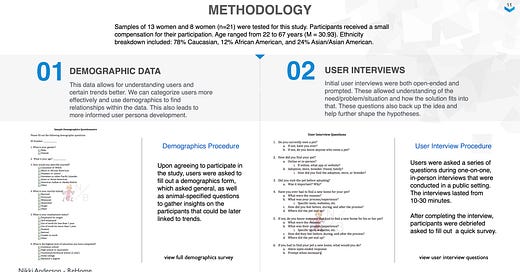

This case study was rife with issues, mostly about my actual skills (look at those beautiful graphs for qualitative interview answers, lol), but also because it lacked the fundamental information I needed to convey in a case study.

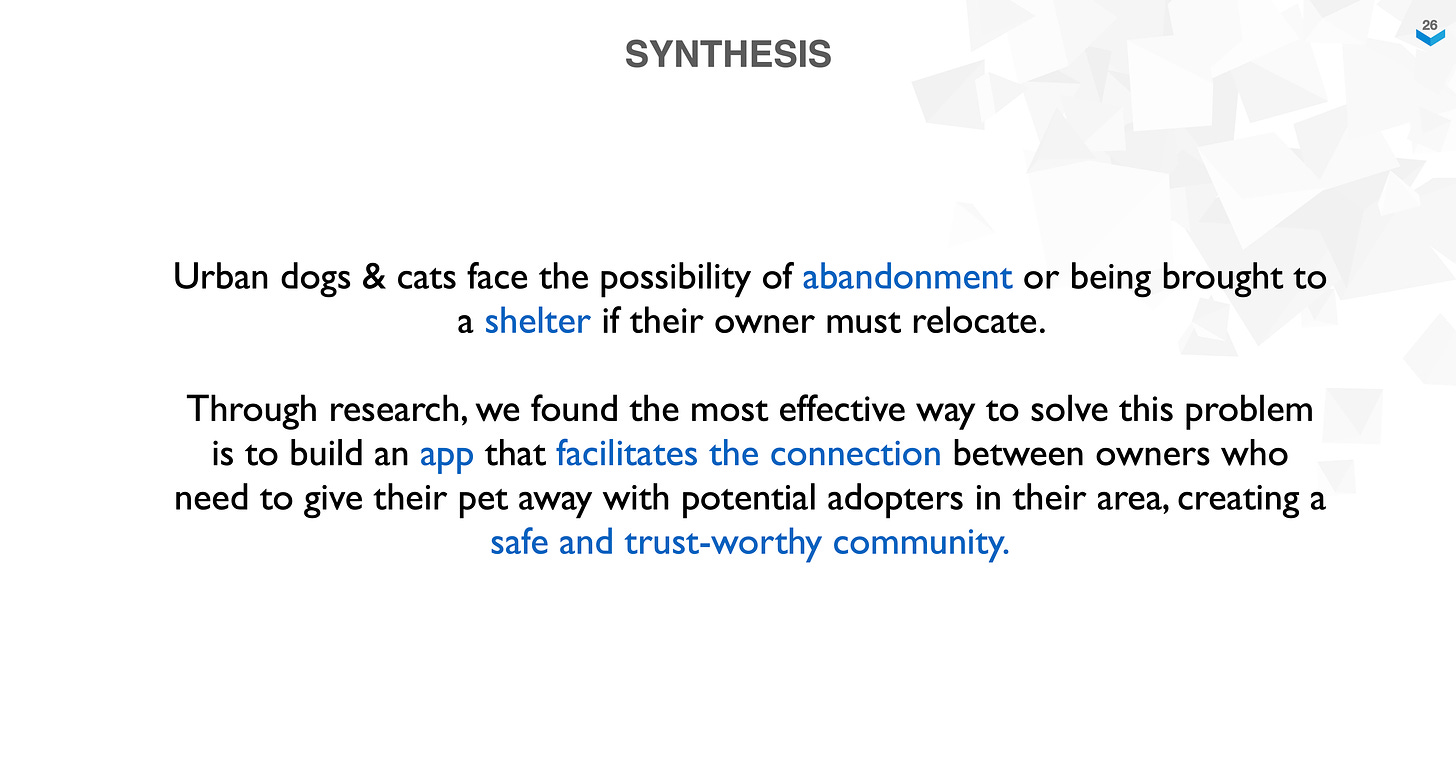

And I had to save this slide for last:

My synthesis wrapped into a few sentences that “proved” we had to build an app. 😂 That’s exactly what you want to hear from a “generative research study.”

After many rejections (yet eventually one acceptance, woohoo!), I was so sick of case studies. I never wanted to look at or think about a case study again. Unfortunately, case studies only became more popular as part of the UXR hiring process. And after some time, I realized I had to dust off my case studies and dive back into more applications.

However, I still hated case studies and found them horrible. They were shrouded in mystery. I didn’t understand case studies and why I had to go through such a horrendous process of creating them.

Fast forward about seven years, and my sentiment toward case studies is completely different.

They don’t have to be horrible.

Case studies are a representation of your most impactful work. Of the work you are most proud of. The kind you want to shout from the rooftops about.

To combat my bad feelings about case studies, I did quite a lot of research on them, as well as experiencing firsthand what it was like to be a hiring manager reviewing case studies. I’ve brought together as much knowledge as possible on this topic to unveil the mystery and make it possible for everyone to create an impactful case study they feel good about.

Let’s get it right — what is a UXR case study?

Case studies are a very special part of the user research interview process. I’ve seen them get slightly confused with UXR portfolios, so I want to share my quick definition and how I will be using the words in the rest of this article.

A case study is a walk-through of a project you completed. In the case study, you talk through the end-to-end process of the project (or initiative) to showcase what decisions you made, how you made them, why you made them, who you worked with, and the impact of the project.

A portfolio is a collection of these case studies. Whenever I get asked how many case studies one should have in their portfolio, I recommend three:

A generative-based case study

An evaluative-based case study (or mixed methods)

A bonus case study on anything you would like

The three case studies that I have most recently used include:

A Jobs to be Done case study that was highly generative

A mixed methods case study on how GenZ get inspired for fashion

A case study on how I increased the user research maturity at an organization by setting up a user research practice

When choosing your case studies, I recommend choosing work you are proud of and passionate about. Work in which you can thoroughly share your process and your decisions. And, work that you want to do in your future role.

For example, I usually don’t share much usability testing work anymore because I don’t want to be doing usability testing. Instead, my sweet spot is coming in as a first and solo user researcher to set up a research practice at an organization and move the research maturity forward.

What’s the point of a case study?

I believe case studies are a great way for hiring managers to assess how a person approached a problem, made decisions, and thought through a project. Not everyone agrees with that, and that’s fine. As a hiring manager, I have found them extremely helpful in assessing candidates.

Now, regarding the more “selfish” reasons for a case study, I would also say they are great. Case studies give you the opportunity to reflect on your projects, see what you accomplished, and pinpoint areas you would improve upon next time (or if you had fewer constraints).

They are a way for you to review your process and understand what steps you went through and the decisions you made. By reviewing your projects and mapping out your steps, you can get more comfortable with your unique research process. Although they can be a slog, I have found creating case studies to be incredibly rewarding internal work on navigating problems as a user researcher and how I’d like to improve.

Now when it comes to what a case study is, I will start first with what it isn’t:

A vague overview of your general user research process. I’ve seen a lot of case studies that just state someone’s process they go through. This usually looks like a process taken off a website and is typically idealized. Unfortunately, this gives none of the nuances of how you approach a problem and do research in the face of constraints. General frameworks aren’t always applicable.

A bunch of different projects strung together that aren’t in-depth. I’ve also seen a case study comprised of about ten pages and, within those ten pages, are about three different projects, each with two or three slides. Within this case, it is impossible for an interviewer to get a sense of your actual thought process throughout a project.

Wireframes, designs, and prototyping, unless you want to be a designer and researcher! You don’t have to include these things in your case studies unless you want to. As a research hiring manager, I seek research-related information, not designs and prototypes.

So, when it comes down to it, what is a case study?

A detailed deep-dive into a project that highlights your decision-making, thought process, and collaboration with others.

A project that is impactful to the organization, product, or your research process. This doesn’t mean the project had to have some profound impact on metrics or a change to your product, as, often, those things are out of our control. However, there are many ways to demonstrate impact outside of the product, including how the project impacted your own research process. Get creative here!

A project that you care about and are proud of that demonstrates your capabilities. Many people have more than three projects to choose from regarding case studies. Think about the projects you were most passionate about and the ones you were most proud of that demonstrate your skills. Passion comes through the screen and infuses itself into the interview. When you want to tell the story of a project, it shows.

A project that showcases the type of work you want to be doing in your future role. The type of work you share is ideally the type of work you will be doing in your next role. As I said, I rarely (if ever) will share work that I don’t want to be doing. So, I don’t share much usability testing or democratization because neither particularly appeals to me. Share the type of work you are passionate about and want to bring into your next role. If they don’t want that work, you don't want to be working there!

When it comes down to it, case studies are a detailed recount of your project that shows (doesn’t tell) your skills as a user researcher.

What are hiring managers looking for in a UXR case study?

For a long time, I had no idea who my audience was and what they were looking for in my case study presentations. As you can imagine, this led to a lot of problems. I presented the wrong information and depth of projects while leaving out essential parts of my process.

Because I lacked confidence in what a case study was and what my audience wanted from them, I rushed through my case studies. I would try to generalize and use idealized examples. I didn’t go much into specifics or my thought process. With that, I got turned down a lot at this stage.

If you think about it, your audience is usually a hiring manager or a group of people you will work with.

Those people are trying to make a decision on whether your process and approaches work and are a good fit for the organization (big note: this is not about YOU as a person necessarily, but how you’ve approached projects in the past).

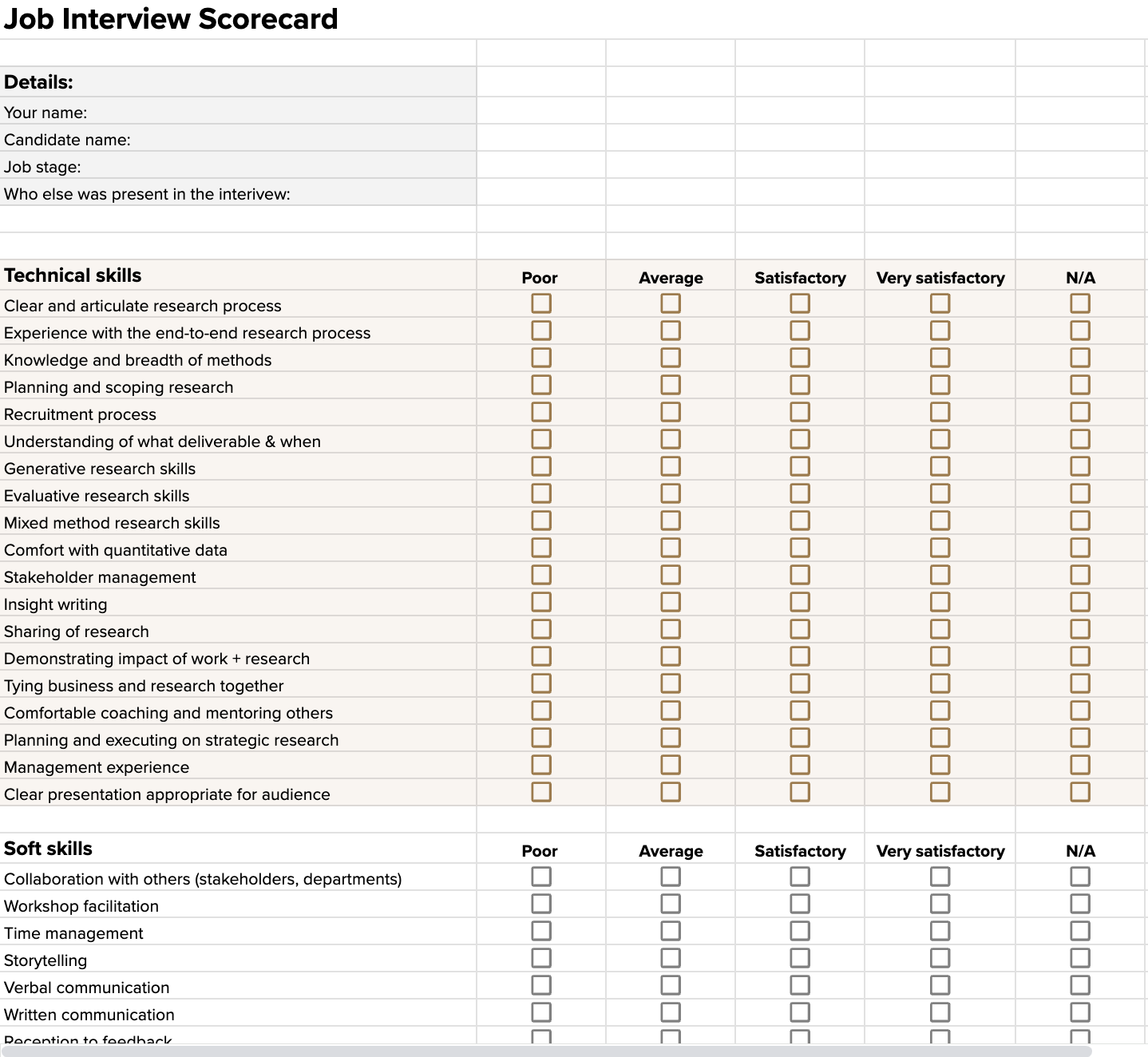

They are assessing your fit. They are trying to make a difficult decision. They might be using a scorecard to rate different areas of your work.

When I realized this, I stepped into the shoes of my audience as best I could. What were they trying to understand? What were they assessing? What decisions were they trying to make?

How might I make the job decision process as effective, efficient and satisfactory for them as possible?

How could I make my side of the process as usability-friendly as possible?

Looking at my case studies from this vantage point not only granted me to take an objective step back (which can be supremely helpful when writing them), but it also gave me a different perspective to understand they type of information they needed from me.

Interviewers are looking to assess:

Your step-by-step approach when dealing with a problem and a potential user research project

How your work has impacted an organization in the past

How you collaborate and work with others during your projects

Why is this information important?

They aren’t gathering this information to judge you as a person or to say your process is wrong or bad — at least hiring managers should not be doing this. A good hiring manager is gathering this information to understand how you might operate in their organization and to determine if that would be a good fit or not.

You know how, as researchers, when we go into a generative research session, we want the user to tell us all the things? We want a snapshot of their thought process, a documentary of their decisions and why. As a hiring manager*, I want something similar from my candidates when they go through their case study.

I want to end a case study interview with as much information as possible to make the best decision for the candidate and the organization.

*Just as a huge PS: I am talking about my experience as a hiring manager and the experiences I’ve gauged from other hiring managers. This isn’t all-encompassing of the hiring managers you will meet. Some differ hugely. The best thing you can do during this process is try to understand their expectations to best give them the information they need.

Biggest mistakes I see (and have done)

I’m the first to admit I have made many mistakes as a user researcher, especially with my case studies. And, as a hiring manager, I have also seen these mistakes repeated many times.

Mistakes aren’t inherently a bad thing. In fact, they are the place where we learn and improve. I always refer to the Pippi Longstocking quote:

“I have never tried that before, so I think I should definitely be able to do that.”

Mistakes give us opportunities to learn, both from ourselves and from others, which is why I find it so important to share my mistakes with others. It might help someone avoid them in the future.

That said, here are the biggest mistakes I’ve made and have seen when it comes to creating and sharing a case study:

Using a report as a case study. Guilty 😆 Way back when I assumed I could just use a report I had presented to stakeholders as a case study. Nope. Not quite. The problem was that a huge chunk of my report was insights. Insights that had no relevance to my interviewers. I was telling them information they couldn’t understand and didn’t care about. Insights aren’t important to hiring managers - now, how you get to them is interesting.

A bunch of photos with no explanatory text. There are three places where your case studies will appear: on your website (I’ll talk about this later), in your application (if you were asked for one), and in a presentation setting. If you leave a case study on your website with only a few photos with limited text, how is anyone supposed to judge that? If you apply with your photo-heavy case study, and I’m using that to understand if I should invite you to an interview, it makes my job harder. And, complete honesty here: if I get a portfolio with several case studies with minimal text and just photos with generic information, I will likely pass.

No explanation of your detailed process. I used to do this all the time. Something weird happens with these project walk-throughs because, suddenly, you went from interviews to insights! There was some magic thing in the background that took raw data and turned it into insights and impact. A lot of people skip over important parts of their process — I want to know how you analyze and synthesize information, so if you don’t share that with me, I can’t know it.

No reflections on the project. I love it when people reflect. It demonstrates to me that they care about improving their craft. So, this might be a particular thing for me, but I really enjoy hearing about how people might have done something differently or changed a project. To me, this is especially important if you are dealing with really intense constraints or things that did not go as well as planned.

Missing some sort of impact. As I mentioned, your impact as a user researcher doesn’t have to be tied to a product or the product team. We aren’t the chef, but an ingredient in the pie — if someone decides to leave something out, we have no control over the outcome. Talk through different types of impact, such as teaching the team, experimenting with a new intake document, running a different type of workshop, increasing the speed of your recruitment, or finding a new tool — there’s a world of impact out there!

Here is an example of a case study I’ve used that wasn’t great:

In this case study, I made quite a few errors, including:

Didn’t talk through the research problem or goals

Went straight into “insights” (which weren’t insightful)

Focused a lot on designs

Didn’t talk about important parts of the process (skipped all the good stuff and rushed to what the thing looked like)

See if you can spot more mistakes 😆

If you’ve made these mistakes, I am here for you!! If you are currently in the process of making these mistakes, it’s okay!! We all make them. Use these moments to learn, improve, and remind yourself that this process is iterative!

What to include in a case study

Let’s get down to the nuts and bolts of it all and explore what to include in a case study, with some examples of good and bad.

Background on yourself. During this moment, you can give a small introduction about yourself and something maybe not work-related or something outside your resume. Some of what I like to share are things like what has changed about me in the past five years, my favorite book, my favorite hobby, or a favorite memory.

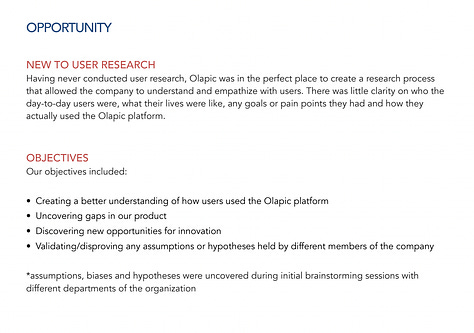

Context on the organization and project. This is where you can give a short introduction to the organization you will be talking about. This doesn’t mean you have to tell people the name of the company, you can just give an overview of the industry and business model (e.g. b2b social media management platform). Finally, briefly introduce the project topic you will be talking about. Remember not to use any jargon from the industry that others may not understand. This grounds hiring managers in what will be coming.

Where the project came from. This portion is often skipped, but super relevant. When you started the project, where did it come from? Was it someone’s idea in the shower? A past research project insight? A pain point someone heard from customer support? And then, how did you decide this was a project worth working on? This helps hiring managers understand the context behind the project and how you prioritize projects.

Your role & others you worked with. Here you can talk about your particular role in the project — did you lead it, work with a team, or work as a support? Who else did you involve in the research project, and how did you involve them? You don’t need to give every detail of collaboration here because it might not be relevant (e.g. you can share about an ideation workshop collaboration later on), but this gives hiring managers context about who you include in your research.

The timeline. In this section, you can give an overview of the timeline of the project. I also recommend breaking the timeline down into different phases (e.g. planning, recruitment, conducting, etc.). Not only does this give hiring managers a holistic view of everything you did (and what you will talk about), but it also lets us understand how you think through different parts of the process.

Research statement/problem & goals. Now we get into the nitty-gritty of the research part - exciting! In this section, you dive into the research problem/question you were trying to answer and the goals you decided on for the research project. This shows the planning portion of the research project and how you think through structuring a request/project.

Success criteria. Success criteria can sometimes be difficult to create but is incredibly important. It helps us answer, “How will we define this project as a success?” This success criteria can be anything from moving product metrics (e.g. how often someone uses a feature), team metrics (e.g. acquisition rate or pirate metrics), or more internal research impact (e.g. identifying top five pain points). This section gives us an idea of how you think through the potential outcomes of a project.

Chosen methodology. Based on your goals, what method(s) did you choose and why? What led you to choose whatever method(s) you did, and did you consider others? Who else was involved in the method-choosing process? This section gives us an idea of how you stitch goals to a given method to ensure you get the best information you need.

The recruitment criteria and process. Who did you choose to talk to to get the information you need to fulfill your research goals, and how did you get them? I recommend sharing screener criteria here (if you can) and your sample size and any thoughts about sample size. By talking through recruitment, which is always a tough part of the process, you show hiring managers how you get the right people for your projects.

Sample questions asked or usability tasks. Whenever you can, it’s great to share concrete examples. If you are able to, I recommend sharing some questions from a discussion guide or survey, usability testing tasks, or any other example of a handful of questions you asked. Since this part is usually something hiring managers struggle to “grade,” it would be fantastic to share how you create these questions. It gives insight into your technical skills as a moderator.

Analysis and synthesis process. This is the part that most people skip and is shrouded in mystery. Somehow we go into a methodology, et voilà, we have insights! Since this is such an integral part of the research process, it is critical to talk through how you analyze and synthesize raw data into something useful and valuable to your team. What types of techniques and processes did you use? Did you debrief after each of the sessions? Why/why not? Who else was a part of the synthesis process? Include examples and screenshots, even if that means you have to blur out sensitive information!

Outputs & deliverables. During this part, you can talk about what actually came out of the research and, if possible, share screen shots. Was it a report or something else (or both)? And how did you choose the outputs and deliverables? Why were those your choice? This section shows hiring managers how you bring the research together into something you can share with others.

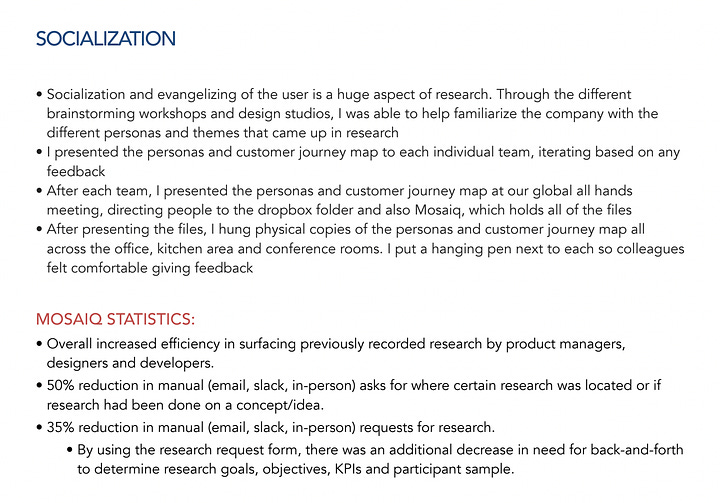

Sharing and activation. During this part, you can discuss how you shared and socialized the research to the larger audience. How did you turn the insights into something the team could act on? What types of workshops did you run? This area shows hiring managers how, as a researcher, you help empower stakeholders to use your research.

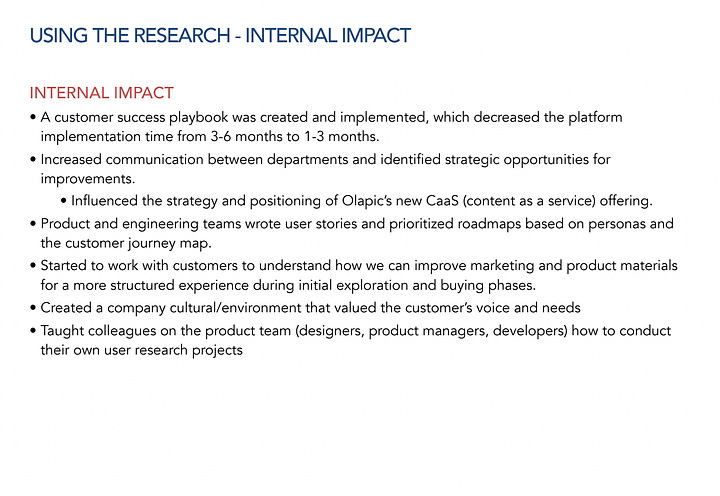

Impact. What was the impact your research had on the product, team, organization, internal research processes, and/or on you? Remember to get creative in this section - it doesn’t have to be about the product! Who used the insights, and how did they use them? What changed because of your research? Speaking about this allows hiring managers to understand how you bring impact with your research.

Next steps/recommendations. This part touches on anything that will come or came after this particular research project. What are the next steps after the research? What is the follow-up? What recommendations did you make to the team and organization? This section helps demonstrate that you try to make research a continuous part of the process.

Your reflections and learnings. As I mentioned, I love this part because, to me, it shows that you are willing to reflect on what happened and look to improve. In this section, talk through what you would have changed, what you learned, and always end on a positive note with what you accomplished/what went particularly well.

Please remember that these are suggestions from my experience and what I’ve used in the past — you might have different things to include, choose not to include certain aspects, or vary the order. This is in no way formulaic! Pick and choose what works best for you 😊

You can find a small example of how I might outline this based on one of my case studies below:

Steps to creating your next case study

Now that we have all the components, how do you create your case study?

The steps I went through that I recommend include:

Look at some job descriptions you like and the types of skills they are looking for, or the responsibilities you will have

Think about your next role and what you want to do in that next role

Pick 2-3 projects that you are proud of that both demonstrate the skills in the job descriptions and are relevant to what you want to do in your next role

Focus on one project at a time

BRAIN DUMP INTO A GOOGLE DRIVE

I cannot stress this enough. I highly recommend not trying to create the perfect document or case study. As Ernest Hemingway says:

“I rewrote the first part of A Farewell to Arms at least fifty times. You’ve got to work it over. The first draft of anything is shit.”

So let’s channel Ernest Hemingway. The best thing you can do is brain-dump absolutely everything you remember from that project. Like, everything. Write all the nitty-gritty details. Trust me. It is so much easier to cut than add.

Typically this takes me about four to six hours to get everything down — not in one sitting — and make sure I’ve thrown everything into that Google Doc. Only after that is done do I start to clean it up and section things out.

Once that initial information is out, I typically section out the information into the above components. If you’re feeling lost with this, you can use my template that lists out all the components as well as probing questions that go along with them.

Only when I have a thorough outline do I put it into my two different formats (which I talk about below):

Slides, which include more screenshots and less text

On my website, which includes a lot of text and screenshots

Here are some screenshots from a case study I’ve used successfully:

What’s great about this process is that, since you have so much information in the document, you can use that as a bit of a script for your interview.

If you want to dive super into case studies, including more examples of the good and bad, with explanations, and a template, you can check out my case study starter kit.

Presenting your case study

There are a few things that you can do both before and during your case study presentation to make it as successful as possible:

Read the job description. It is crucial to be familiar with the job role and the expectations before choosing your best case study. In this way, your case study is a little like a cover letter. The projects and skills you choose to highlight during the presentation should be aligned with what would be expected from you in the role you're applying for.

Research the company. Keep in mind the goals and context of the company. For instance, if you are interviewing for a B2B position, choose to present B2B case studies or case studies that showcase the most relevant skills. Knowing the company's purpose and vision can help you talk about how you have strategically tackled similar concepts in the past.

Research the team. Try to find out information about the team you will be joining. They may have a page where you can see what type of research they do or their vision as a team. If not, this is a great question to ask after your presentation!

Leave time for their questions AND your questions. This ensures that your interviewer can ask the necessary questions to make the best decision about your next step. For example, a 1-hour case study presentation = 35-40 mins of you presenting, 10 mins for their questions, and 10 mins for yours.

How to speak impactfully

I’ve mentioned a few times how important it is to make impactful statements to demonstrate how valuable the research you did was and also to highlight why you did something and collaboration points.

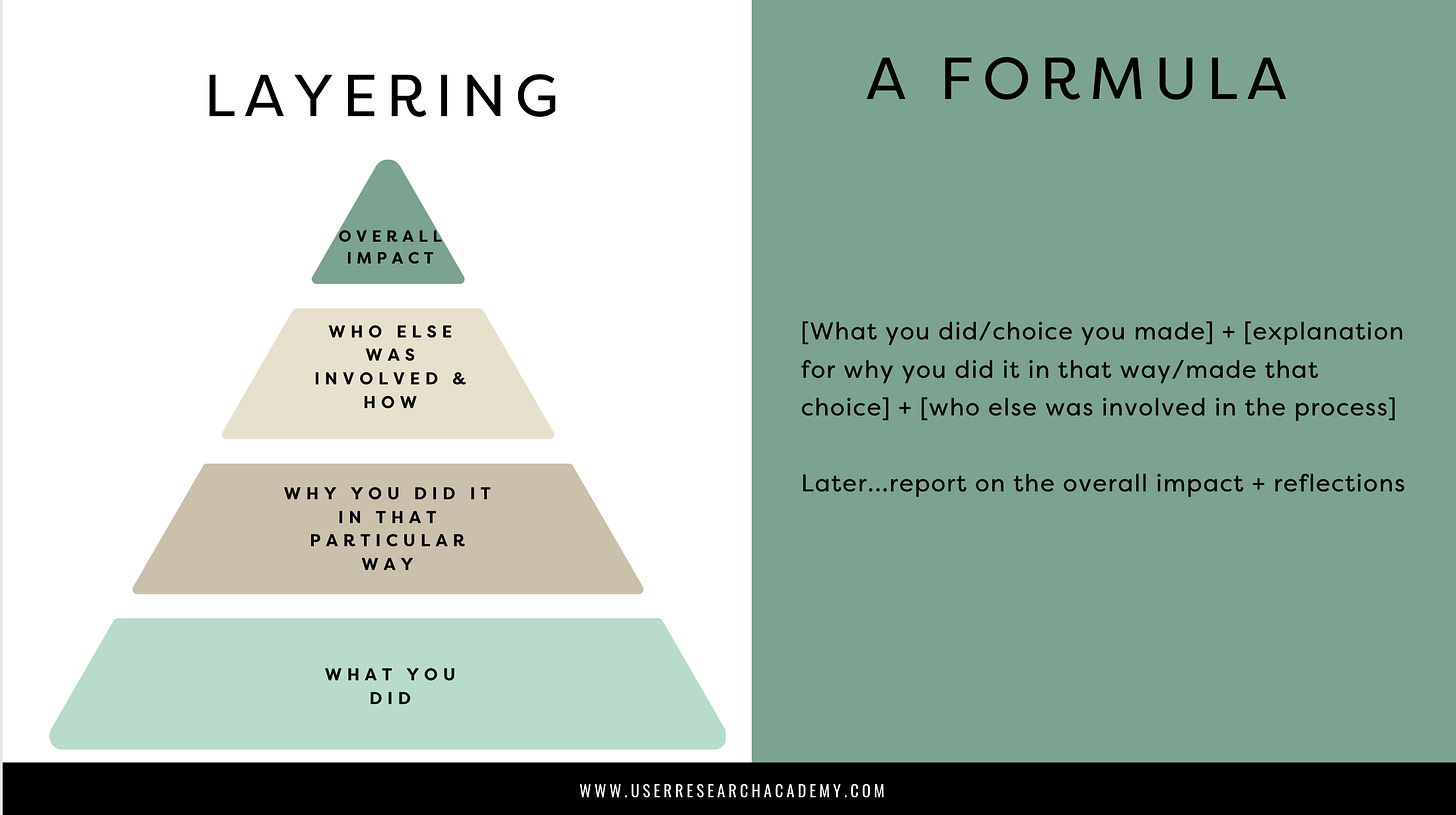

Not only is this a lot to remember at once, but you are already in a fairly high-stress situation — unless you love interviews which some people do! — so I created a formula to help you remember. You can jot these formulas down directly into that Google Doc you used for outlining:

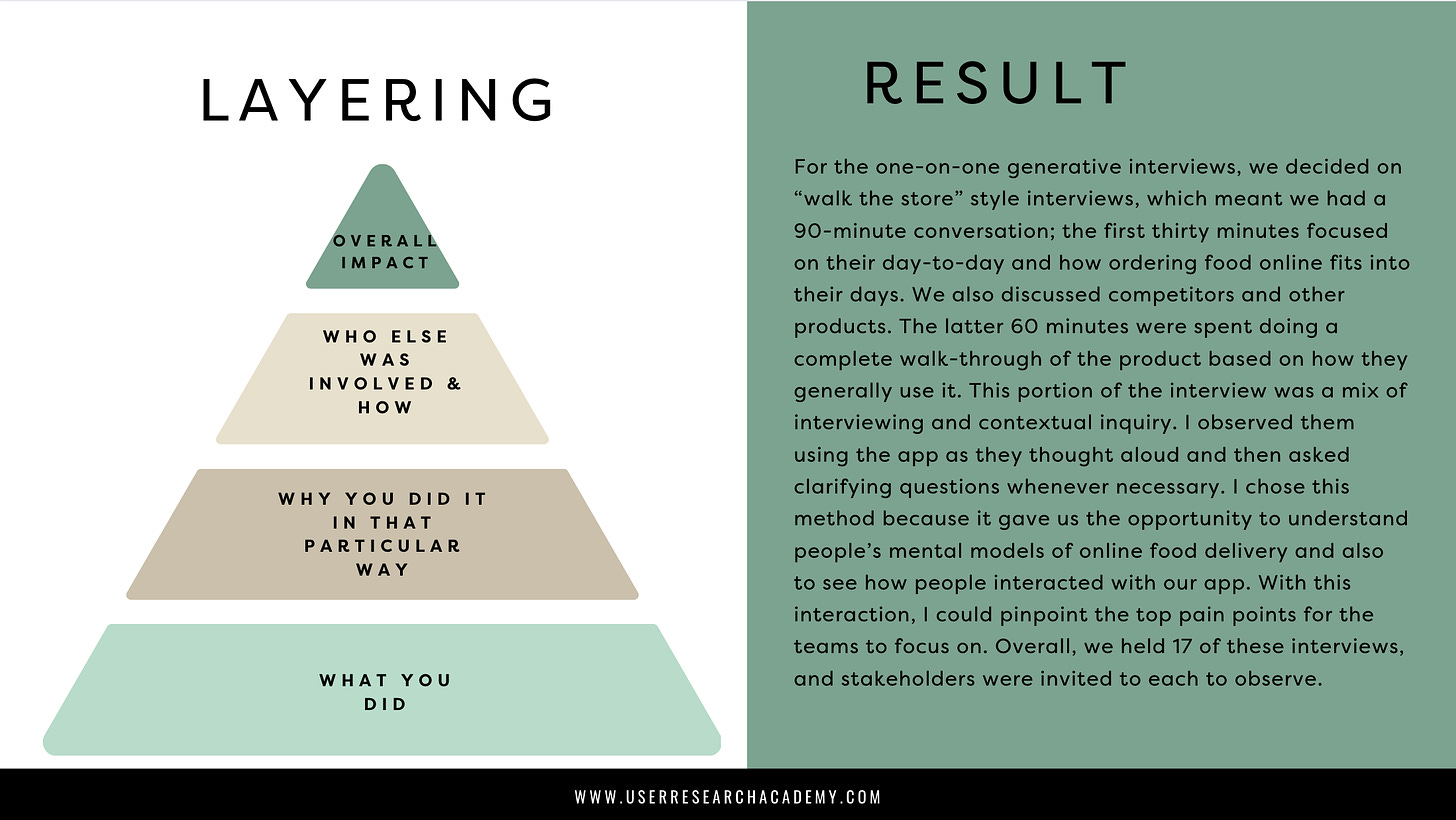

[What you did/choice you made] + [explanation for why you did that/made that choice] + [who else was involved].

Using this formula helps ensure that when you are talking through your process, you give all the juicy details that hiring managers want to hear.

See below for a few examples of how I’ve taken a less-than-ideal statement that doesn’t give much context and added more to it so that it is fully formed:

Not ideal: We recruited 25 people for interviews

Better: We sent a screener survey to 250 people through our marketing email to get at least 25 interview participants for this generative research study. Inside that screener survey, we assessed the following criteria:

People who have moved to a new apartment in the past three to six months (to get their recent experience)

People who have visited at least three apartment viewings in the past three months (to get current experience)

Not ideal: After the interviews, I created two personas

Better: After each interview, I held a 30-minute debrief with stakeholders to help us synthesize during the project. We used an affinity diagram highlighting the needs, goals, and pain points from that particular interview. I decided on these tags as they were the most relevant information for the persona deliverable and the information stakeholders needed by the end of the project

I then tagged the transcript using those global tags to ensure we didn't miss anything in the debrief.

After every five interviews, we had a larger synthesis session to gather the past five participants to see trends and patterns across interviews. We did this, as well, through affinity diagramming.

After we completed all the interviews and synthesis, I held an activation workshop where we pulled the information from all 20 participants and started to sort through similarities and differences - we sorted this through spectrums of their needs, goals, and pain points. Ultimately this resulted in two distinct personas.

You don’t need to make everything you say into a hugely impactful and detailed statement because you do need to think about your time limit. I recommend trying some of these out and, as always, practicing presenting your case study. My go-to, as cringe as it is, is recording myself presenting something and listening back to see where I can improve.

After your presentation

Once your presentation is over, there are a few key things you can do that I’ve found help with the success of my current presentation and also others:

Have a list of questions ready to ask your interviewer, both that you brainstormed before and also maybe some that you thought of when you got more context. Some great questions include topics like:

Struggles the hiring manager has had

The best part of working at the company

The hardest part of working at the company

What the team is like (team culture)

What the team does to bond outside of work

Who the hiring manager works with on a daily/weekly basis

How the organization/team deals with mistakes

Send a thank you email to the person that you spoke to, either directly or to your contact, who can forward it to them. This doesn’t have to be a lengthy note, but something simple like, “Thank you so much for your time talking to me. I appreciated the X or Y question you asked and the Z moment. Looking forward to hearing from you.”

Reflect on how it went, including what went well during the presentation and any wins you had, as well as any opportunities for improvement. Use that time to tweak anything for the next round!

Formatting, hosting, and NDAs

Some of the more nitty-gritty questions I get asked are about formatting, where to host case studies and NDAs. All of these are a bit intertwined and depend on each other. I will talk through my experience, but I recommend talking to others to see what’s worked for them.

I’ve always hosted my case studies on a Squarespace website. I put them on a webpage and as a downloadable PDF. Regarding the presentation, I turned the PDF and information into a slide deck (usually on Google Slides).

The reason I put my case studies on a website is because I find that some job applications ask for a website, and others ask for an attachment. I was also a freelancer for some time, so having a place for people to view my work and see what I was all about was critical. I recommend having a website with your work and a bit about yourself.

In terms of NDAs and sharing work. Some of my case studies are available online because either:

It’s been so incredibly long

The company no longer exists

I got permission to share this information

There are some case studies I don’t have or that are password protected. For these case studies, I only share them during the presentations I have. This is because I didn’t get permission to share them publicly.

When it comes down to this, I recommend checking your contract and with your legal team to see what works best for you. If you can’t openly share your work, that’s okay. I still recommend having a website available that’s about you and letting people know they can contact you if they want you to share work with them.

And, during the presentation, if you are concerned about information, please don’t share it. Remember, your case study isn’t about the particular organization and the insights you found, it’s about you and your thought process. Wipe any sensitive data. You can also not name the company — hiring managers have usually been there themselves, we get it!

You can always check out my case studies (some better than others!) here.

A note on rejection

I used to get so upset when a job rejected me. It played against my insecurities, and I immediately felt worthless and like I would never be good enough. And, yes, this happened every time I got rejected for a while. And I got rejected an awful lot.

However, I once took a job in which I should have been rejected (and I should have also rejected them). I wasn’t a good fit for the job, and the organization wasn’t a good fit. I had to quit almost immediately.

After that, I realized I didn’t need to take rejection personally. Of course, if there were ways for me to improve my craft and my interviewing, I would take those into consideration. But, sometimes, you just aren’t the right fit, and that can be a really good thing.

Whenever you get rejected, I recommend asking for feedback (you rarely get it, but it is worth asking), and then carving out some time to reflect on the interview process and if there was anything you felt you could do better. If so, practice those skills. If not, you spent all the energy you needed thinking about it!

To this day, I get rejected from conferences, company workshops, and freelance opportunities. It’s about understanding you won’t be a perfect fit for everything/everyone, and that is okay.

Join my membership!

If you’re looking for even more content, a space to call home (a private community), and live sessions with me to answer all your deepest questions, check out my membership (you get all this content for free within the membership), as it might be a good fit for you!

This is so detailed and practical. Thank you much Nikki!